This World’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, held in Chicago, was designed to commemorate the 400th anniversary of Columb us’ discovery in the New World, but as is typical in large ventures, the fair was delayed until the following year (Butko). This fair was where the World’s Parliament of Religions was held, introducing Americans to Hinduism and Buddhism through the Swami Vivekenanda and Anagarika Dharmapala (Hedstrom). At the same time that America was being introduced to new forms of spirituality, new products in the commercial sphere were on display just a few buildings away. H. J. Heinz took advantage of this largest of stages to pitch his ever-changing line of products which appealed “to America’s tastes and eating habits (Butko).” Beyond just free samples, H. J. Heinz was marketing his brand. There were photos and descriptions of his “food processing factory, a marvel of modern amenities and advanced technologies (Butko).” The appeal of his products— “horseradish, ketchup, jams, even vinegar”— went far beyond the items themselves. Heinz was selling modernity and convenience. Traditional home preparation of these same foods “consumed long hours and hard work,” but Heinz was offering pre-made, high quality replicas for large-scale consumer markets (Butko). The lynchpin in Heinz being able to do this was his combination of quality control at home, using his own produce grown on his own land, and “the expansion of the railroad and the advent of refrigerated freight cars (Butko).” Heinz’ embrace of new technologies created a demand for his products as he was one of the first to mechanize labor-intensive foods and sell them widely.

us’ discovery in the New World, but as is typical in large ventures, the fair was delayed until the following year (Butko). This fair was where the World’s Parliament of Religions was held, introducing Americans to Hinduism and Buddhism through the Swami Vivekenanda and Anagarika Dharmapala (Hedstrom). At the same time that America was being introduced to new forms of spirituality, new products in the commercial sphere were on display just a few buildings away. H. J. Heinz took advantage of this largest of stages to pitch his ever-changing line of products which appealed “to America’s tastes and eating habits (Butko).” Beyond just free samples, H. J. Heinz was marketing his brand. There were photos and descriptions of his “food processing factory, a marvel of modern amenities and advanced technologies (Butko).” The appeal of his products— “horseradish, ketchup, jams, even vinegar”— went far beyond the items themselves. Heinz was selling modernity and convenience. Traditional home preparation of these same foods “consumed long hours and hard work,” but Heinz was offering pre-made, high quality replicas for large-scale consumer markets (Butko). The lynchpin in Heinz being able to do this was his combination of quality control at home, using his own produce grown on his own land, and “the expansion of the railroad and the advent of refrigerated freight cars (Butko).” Heinz’ embrace of new technologies created a demand for his products as he was one of the first to mechanize labor-intensive foods and sell them widely.

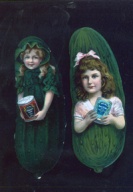

H. J. Heinz understood American consumerism better than Americans themselves. Grocers often were the most direct way to sell a product, and Heinz developed advertising campaigns for grocers to more effectively  communicate his products (Maloney). He also “made products aimed at different price points,” understanding American consumers’ desire for variety and choice, ensuring they had the product they wanted for the price they could afford (Butko). His ubiquitous brands and labels, his “57 varieties,” posted everywhere, from wagons to bridges, and his famous “pickle pins” he distributed at the World’s Columbian Exposition, all helped to make the Heinz brand an identifiable American icon and name (Butko). Heinz and his partners opened up their state-of-the-art facility

communicate his products (Maloney). He also “made products aimed at different price points,” understanding American consumers’ desire for variety and choice, ensuring they had the product they wanted for the price they could afford (Butko). His ubiquitous brands and labels, his “57 varieties,” posted everywhere, from wagons to bridges, and his famous “pickle pins” he distributed at the World’s Columbian Exposition, all helped to make the Heinz brand an identifiable American icon and name (Butko). Heinz and his partners opened up their state-of-the-art facility for tours, and then their own chemistry lab to make sure their products were as pure as possible (Butko). The company was a major proponent of food safety in a time when few to no laws existed to monitor and regulate food manufacturers (Gaughan). All that would change with Harvey Washington Wiley and FDR’s administration, with the support of food producers like H. J. Heinz (Guaghan).

for tours, and then their own chemistry lab to make sure their products were as pure as possible (Butko). The company was a major proponent of food safety in a time when few to no laws existed to monitor and regulate food manufacturers (Gaughan). All that would change with Harvey Washington Wiley and FDR’s administration, with the support of food producers like H. J. Heinz (Guaghan).

Sources:

- Butko, Brian. “Heinz – Much More than 57 Varieties.” Pennsylvania Heritage Spring 2012: n. pag. Pennsylvania Heritage. Spring 2012. Web. 29 Nov. 2014.

- Gaughan, Anthony. “Harvey Wiley, Theodore Roosevelt, and the Federal Regulation of Food and Drugs.” LEDA at Harvard Law School (2004): n. pag. Web. 29 Nov. 2014.

- Maloney, Sean, and William Cadamore. “Success in Every Bottle: The H.J. Heinz Company.” The Pennsylvania Center for the Book (2009): n. pag. Web. 29 Nov. 2014.